Section 25402 of the Public Resources Code

The Legislature adopted the Warren-Alquist Act which created the California Energy Commission (Energy Commission) in 1975 to deal with energy-related issues, and charged the Energy Commission with the responsibility to adopt and maintain Energy Efficiency Standards for new buildings. The first Standards were adopted in 1978 in the wake of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) oil embargo of 1973.

The Act requires that the Energy Standards be cost effective “when taken in their entirety and amortized over the economic life of the structure.” It also requires that the Energy Commission periodically update the Standards and develop manuals to support the Energy Standards. Six months after publication of the manuals, the Act directs local building permit jurisdictions to withhold permits until the building satisfies the Standards.

The “First Generation” Standards for nonresidential buildings took effect in 1978, and remained in effect for all nonresidential occupancies until the late 1980s, when the “Second Generation” Standards took effect for offices, retail and wholesale stores.

The next major revision occurred in 1992 when the requirements were simplified and consolidated for all building types. At this time, major changes were made to the lighting requirements, the building envelope and fenestration requirements, as well as the HVAC and mechanical requirements. Structural changes made in 1992 led the way for national standards in other states.

The Standards went through minor revisions in 1995, but in 1998, lighting power limits were reduced significantly, because at that time, electronic ballasts and T-8 lamps were cost effective and becoming common practice in nonresidential buildings.

The California electricity crisis of 2000 resulted in rolling blackouts through much of the State and escalating energy prices at the wholesale market, and in some areas of the State in the retail market as well. The Legislature responded with AB 970, which required the Energy Commission to update the Energy Standards through an emergency rulemaking. This was achieved within the 120 days prescribed by the Legislature and the 2001 Standards (or the AB 970 Standards) took effect mid-year 2001. The 2001 Standards included requirements for high performance windows throughout the State, more stringent lighting requirements and miscellaneous other changes.

The Public Resources Code was amended in 2002 through Senate Bill 5X to expand the authority of the Energy Commission to develop and maintain standards for outdoor lighting and signs. The Energy Standards covered in this 'manual build from the rich history of Nonresidential Energy Standards in California and the leadership and direction provided over the years by the California Legislature.

The 2008 Standards were expanded to include refrigerated warehouses and steep-sloped roofs for the first time.

The 2013 Energy Standards reflected many significant changes as well as expanded its scope. Some changes included Fault Detection and Diagnostic devices, economizer damper leakage and assembly criteria, air handler fan control for HVAC systems, updates to the low-sloped cool roofs requirements for nonresidential buildings, and for the first time, set minimum mandatory measures for insulation in nonresidential buildings. Expanding the scope of the Standards included newly regulated covered processes such as: parking garage ventilation, process boiler systems, compressed air systems, commercial refrigeration, laboratory exhaust, data center (computer room) HVAC, and commercial kitchens.

The 2016 Energy Standards are current with ASHRAE 90.1 national consensus standards. Changes were made to clarify the Energy Standards and resolve compliance concerns.

Example 1-17

Question

If a building is LEED certified does it still need to meet the 2016 Energy Standards?

Answer

Yes.

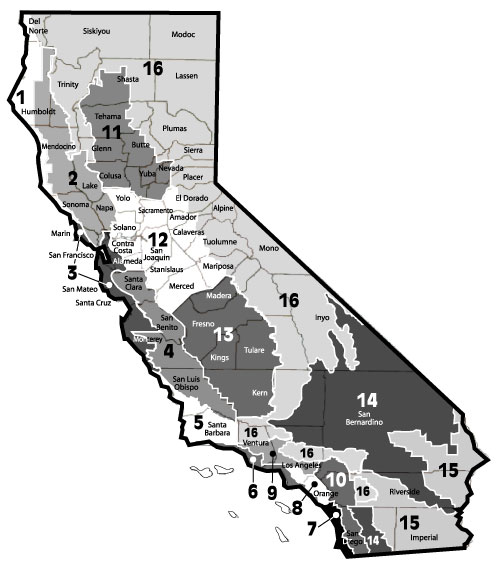

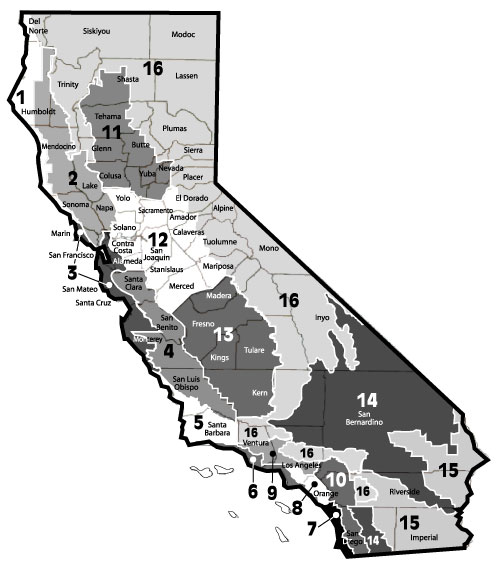

Since energy use depends partly upon weather conditions, which vary throughout the State, the Energy Commission has established 16 climate zones representing distinct climates within California. These 16 climate zones are used with both the residential and the nonresidential Standards. The boundaries are shown in and detailed descriptions and lists of locations within each zone are available in Reference Joint Appendix JA2.

Cities may occasionally straddle two climate zones. In these instances, the exact building location and correct climate zone should be verified before any calculations are performed. If a climate zone boundary line splits a single building, it must be designed to the requirements of the climate zone in which 50 percent or more of the building is contained.